Digital Twins and BIM: built environment management

In recent years, the relationship between BIM and digital twins has shifted from being an emerging innovation to becoming part of a technical conversation embedded in design, operation, and maintenance teams.

The focus is no longer on defining concepts, but on analyzing how these two complementary tools come together in practice to provide real answers to the challenges of managing built environments.

The question is no longer whether to integrate a digital twin into a BIM-based project, but how to do it properly, with what data, at which stage of the life cycle, and with what objectives.

From Data to Behavior

Much of a BIM model’s value lies in its ability to describe the geometry and attributes of an asset in an orderly and accurate way. But when that static information connects with dynamic data — temperature, occupancy, electricity use, structural vibrations — it becomes something else: a representation that not only documents, but also reflects, responds, and anticipates.

That’s what is happening on the Technical University of Munich campus, where several buildings have been equipped with sensors to measure environmental and usage variables. The existing BIM-based digital infrastructure became the foundation for building a digital twin that now allows energy consumption to be managed, failures to be predicted, and HVAC systems to be adjusted before problems occur. It’s no longer just a virtual model — it’s a live monitoring and decision-making system linked to the building’s day-to-day reality.

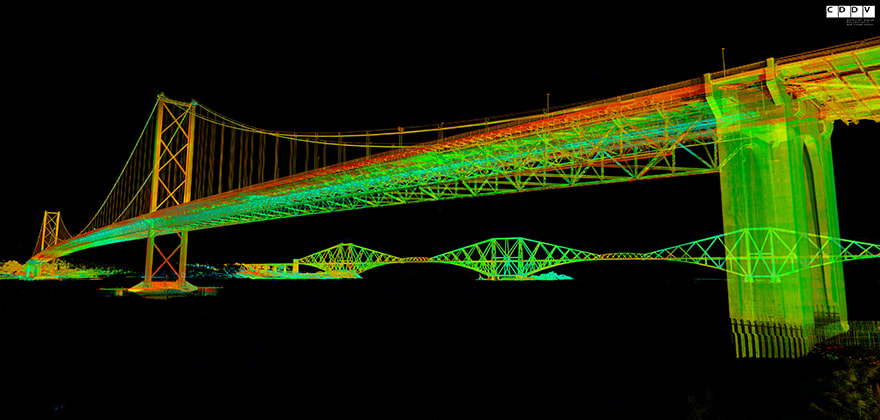

A similar approach was implemented at the Forth Road Bridge in Scotland, where the combination of laser scanning, structural sensors, and digital modeling makes it possible to anticipate material fatigue and plan interventions with precision. After six decades in service, the bridge now has a digital counterpart that doesn’t just represent it — it listens to it.

Urban Simulation and Policy-Making

Urban-scale projects come with different challenges: more stakeholders, more data, more layers of information that must interact. But they also open up possibilities — among them, using a digital twin as a tool for urban planning and public management.

Virtual Singapore is a landmark case. This platform integrates BIM models and GIS systems into a 3D digital replica of the entire city. It enables simulations as varied as emergency evacuations, pedestrian flows in dense districts, façade thermal behavior, or neighborhood-scale energy efficiency. Far from being just a demo for institutional presentations, this urban twin functions as a working tool for public agencies, private firms, and academic institutions alike.

BIMCommunity explored this case in depth in its article on the integration of BIM and GIS in Singapore, detailing how this fusion of scales and technical languages supports more informed decision-making in complex urban contexts.

What Works — and What Still Doesn’t

While progress is evident, implementing digital twins on top of BIM models still faces real-world challenges. Interoperability between platforms isn’t always smooth. Data often lacks the quality required to feed real-time systems. And many teams still view the BIM model as a static deliverable, when its true potential only emerges when it’s connected, updated, and integrated into an operational logic.

The lack of clear standards and contractual frameworks doesn’t help either. Who maintains the model? Who’s responsible for updates? What happens to the data when the building changes hands? These are questions that — as of today — don’t have a single answer, and demand new forms of organization and digital governance.

From Technical Tool to Service Layer

What’s compelling about the convergence between BIM and digital twins is that, when it’s done with intention, it stops being a technological novelty and becomes a change in perspective. It’s no longer about delivering more detailed drawings or better-looking models, but about enabling a service layer that supports the asset throughout its lifecycle.

The projects in Munich, Scotland, and Singapore show that this shift is possible. But they also make it clear that technology alone is not enough — it takes purpose, planning, and institutional commitment. The digital twin doesn’t replace BIM, and BIM doesn’t make the twin redundant. Together, they allow us to move from project control to behavioral understanding.

And in a world that’s only becoming more complex, that can make all the difference.

Fuente: Construnario España